By Anirudh Mathur |27 January 2012

The Dalai Lama spoke to Anirudh Mathur about Chinese protests, the future of the Tibetan movement, the stagnancy of capitalism, and his amazing vitality. The full interview can be found in Outlook Magazine,India:

A Bodhissatva is an enlightened being; one who has postponed their own Nirvana in order to serve humanity. And the 14th reincarnation of Avalokitesvara, the Bodhisattva of compassion, certainly fits this definition. One of the most prominent figures in the world, as the driving force and symbol of the Tibetan movement, and as an “ocean of wisdom” to millions of Buddhists, the 14th reincarnation of the Bodhissatva of compassion needs little introduction. We all know the Dalai Lama.

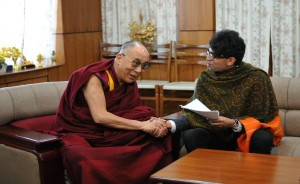

I remember as Frozen Planet drew to a close, a friend on my staircase commented that there could be no one with more trademark warmth than David Attenborough. I thought that if there were one person who could, it would be the Dalai Lama. And his embrace upon my reception, full with beaming smile and characteristic laugh, confirmed this.

The whole process up until that point had been a nightmare. Securing the interview and finding and arranging the freelance had been incredibly time consuming. But speaking to the Nobel Peace Laureate in his tranquil residence in the hill station of Dharamsala,India, as the previous year drew to a close, is something that I could never forget.

I started by querying whether the protest and democratization movements of 2011 would soon extend to China and also whether he thought the forthcoming changes to the Chinese political elite (the politburo standing committee) would affect Tibet’s future.

His frankness and pragmatism was noticeable – 52 years of exile can have that effect. But truly impressive was the genuine optimism that still underlays his thoughts. “Whilst it is difficult to say whether it [the protest movement] will soon extend to China, freedom of speech, freedom of religion and the rule of law are much desired. In China, more voices are being heard for these things – I have met a number of Chinese people, even from the mainland who express such desires.”

Further, regarding politburo changes, he was convinced that although “individuals make a difference, dictatorship, unlike in Burma or Pakistan, is institutionalized in China. The person can change, but the system will remain unless the next leader is very strong, like Deng [Xiaoping].” This would seem to explain his comment why “there hasn’t been much effect despite China’s premier Wen Jiabao saying that China needs a western style of democracy.”

With his trademark simplicity of logic he added, “I met someone from Mainland China and said that if this view of the Chinese premier is wrong, then he deserves punishment. But if his view is right, then it is right to implement it.”

2011 was meant to mark the reinvigoration of the Tibetan movement. With the transfer of temporal power to the newly elected Tibetan Prime Minister, the year raised issues over the long term momentum of the movement, and its potential longevity. A particular area of interest was how Tibetans of the next two generations would carry forward the momentum of the Tibetan movement, given they are technically Indian citizens, and many of their grandparents may not have even seen Tibet.

Acknowledging that this longevity could be a potential problem, he responded, “till now, the movement has been very strong and satisfactory. But the future depends on education and awareness of Tibetan culture and Buddhism.” Would this educational drive and awareness not diminish in the modern day though? “There is promise – interest in Tibetan culture and Buddhism is increasing in many places like Europe and even China. Scientists are showing interest in Buddhist philosophy and ethics and that is reflected upon the younger generation. Today’s Tibetan youth are more spiritual than those of similar age were in the 1960s and 1970s.”

But don’t previous statements by him that issues like climate change are more important than Tibetan autonomy undermine momentum? If he can say this, and he is the figurehead of the Tibetan people, what signal does it send to younger Tibetans who aren’t sure what the real significance or importance of their movement is?

It seems, though, his statement has been mis-portrayed. “I mentioned Tibetan ecology. Politically, once we develop some kind of understanding and Chinese leaders become more mature, our problems are easily solved. But ecologically, the damage is already there, from mining and dams and other such things. Policy cannot change ecological damage that has already occurred. Therefore, the political problems can wait, as the ecological damage will remain forever.”

While maintaining that as per his actions in 1986 and 1987 he would not promote a Tibetan uprising if things got out of control with violence, and instead resign, he felt it more difficult to say whether he could comfortably promote a non-violent uprising that he knew the Chinese would repress with arms.

“I see myself as a spokesperson and not a leader: from March, I handed over political power to the new Tibetan PM. Therefore it wouldn’t be my responsibility; the decision [to promote it] is the boss’s, and the Tibetan people are the boss.”

Astounded at the frustration I am sure he must feel, particularly regarding the situation of those actually in the ground in Tibet, I enquired how he manages to cope. Once more, his optimistic pragmatism shines through.

“We are followers of the Indian tradition. Gandhiji, in most situations, remained smiling. Very occasionally, he’d shout, but mostly he stayed peaceful. That didn’t mean there wasn’t a problem. He’d look at the problem and believed that if the problem could be solved, the effort to solve it should be put in. If it can’t be solved, then it’s possible to be frustrated. I believe the same.”

Moving on to financial capitalism, the antithesis of Tibetan Buddhism in many ways, I was interested to find whether there was almost a sense of vindication for him in the West’s economic decline. Did it demonstrate that a simpler way of life was a better way of life?

“Overall, I feel that—and not just because of this crisis. There is a huge rich-poor gap around the world; also overpopulation. This year, we had the seventh billion person come into the world, next eight billion, and then nine billion. Resources are not sufficient. Ultimately, our stomach needs grain, not more factories and machines. Recently, near Delhi, I saw fields being turned into factories. China has this problem also.”

But the fundamental problem remained overpopulation and the lack of sustainability of our lifestyle, “we can’t all have a US lifestyle.”

Nevertheless, whatever the economic creations of the Western world, and despite noting inconveniences from the West’s consideration that good relations with China are important, he speaks favourably of western help. Rejecting the idea that an economically stagnant West would compromise Tibet by giving China more leverage, he notes that the West always mentions Tibet to Chinese counterparts.

Moreover he expresses that increased Chinese leverage need not be disastrous. “Many Chinese are starting to really believe in democracy, openness and transparency now. These Chinese are also very supportive. In the long run, this change in the Chinese themselves will cause real change for us.”

I finish by asking the secret to his vitality. At his age to maintain such an active and demanding lifestyle is truly incredible, particularly when I consider long weeks in the vac spent eating rice pudding and watching How I Met Your Mother exhausting. Indeed, the day after the interview he was set to travel to Bodh Gaya to deliver a series of ‘teachings’ attended by Buddhists from around the world.

Was it daily meditation, which gave him his glow? Or if not, then surely it came through some metaphysical presence? Apparently, no. “Eight to nine hours of sleep. I go to bed at 6.30 to 7 and wake at 3.30 daily.” It seems that not everything requires hours and years of discipline and dedication.

As he accompanied me to the door, I made sure to throw in that we in Oxford would love to host him when he is next in the UK. “Let me see, if you can make an opportunity for me to come toOxford, then I will.” The Bodhissatva of compassion: coming soon to a college near you?

© Outlook Magazine,India