- An Overview of Sino-Tibetan Dialogue

- Important Statements of His Holiness the Dalai Lama

- Sino-Tibetan Dialogue: A Chronological Account since 1978

- The Middle-Way Approach: A Framework for Resolving the Issue of Tibet

- Memorandum on Genuine Autonomy For the Tibetan People

- Note on the Memorandum on Genuine Autonomy for the Tibetan People

- Recommendations of the First Special General Meeting Convened Under Article 59 of the Charter

- Statements on Sino-Tibetan Dialogue since September 2002 by:

- International Resolutions & Recognitions on Sino-Tibetan Dialogue

- CTA’s Response to China’s allegations

-

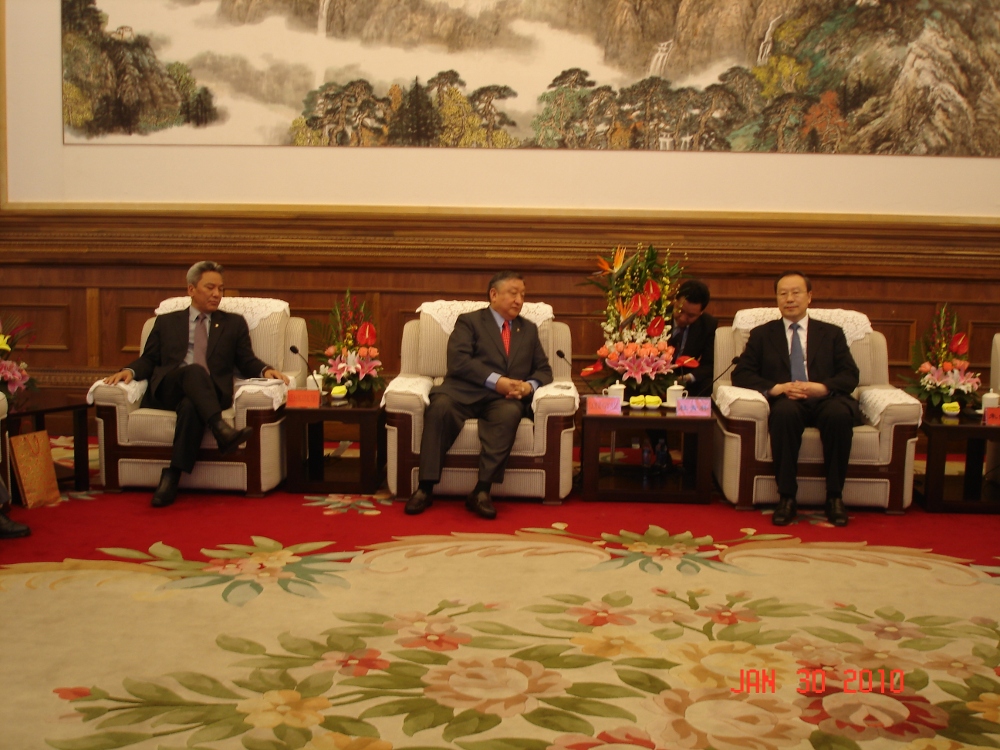

Special Envoy of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Kasur Lodi Gyari (center), with Envoy Kelsang Gyaltsen (left) during their meeting with Vice Chairman of Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference Du Qinglin (right) during their afternoon meeting on 30 January 2010. (Photo credit DIIR/CTA)

No issue is more important to Tibetans than finding a peaceful and negotiated solution to the problem in Tibet.

To this end, His Holiness the Dalai Lama has endeavored for many years to bring Beijing to the negotiation table. The formula that he has proposed for negotiations addresses the worst fears of both Tibetans and China.

The Tibetan people’s deepest concern is the threat to the survival of their culture under the prevailing political dispensation, which has carved Tibet into several administrative units with the western half designated as the “Tibet Autonomous Region”, and the areas of eastern half designated variously as “Tibetan Autonomous Prefectures” and “Tibetan Autonomous Counties”, and merged with neighboring Chinese provinces.

The word “Autonomous” applied liberally to the Tibetan areas is nothing more than a cruel joke on the people, for whom all decisions are made in Chinese national and provincial capitals, and enforced with Stalinist brutality.

In the case of the “Tibet Autonomous Region”, decisions are made from Beijing. Similarly, in the case of Tibetan areas in the east, decisions are made from the capitals of the Chinese provinces into which they are merged.

To address this problem, His Holiness asks for the reunification of all Tibetan areas as a single Tibetan administrative entity, enjoying real autonomy, or local self-rule, within the political framework of the People’s Republic of China.

His offer for Tibet to remain within “the political framework of the People’s Republic of China” is indeed a huge concession and aimed at addressing Beijing’s worst fear, which is the prospect of instability in Tibet and its eventual separation from China. Beijing remains firmly convinced that any attempt to loosen the leash on Tibet would result in a cry for independence.

His Holiness said that if Beijing were to accept his demand for Tibet, he would use his moral authority among the Tibetan people to give up their demand for independence.

Describing this formula as a Middle Way approach, His Holiness explains that if such a solution were achieved, Beijing would no longer have to fear the prospect of Tibet’s secession, just as the Tibetan people’s aspirations to decide their own development would be fulfilled.

His Holiness said that he had come to this decision in the 1970s in a series of closed-door discussions with his cabinet ministers and close aides.

Then, in 1979, China’s paramount leader Deng Xiaoping proposed that other than the issue of Tibet’s independence anything could be discussed and resolved. It seemed that there was a meeting of minds between the two sides; a solution based on the Middle Way approach seemed achievable.

Naturally, His Holiness responded by stating that in view of the prevailing reality of Tibet’s status as part of China, he would not press for independence, but would instead engage in dialogue to find a “mutually acceptable solution”.

In the ensuing years, there were numerous discussions between Tibetan delegates and Chinese leaders, during which it became apparent that the two sides were on completely different wave lengths. While the Tibetan delegates wanted a solution that fulfilled the wishes and aspirations of the six million Tibetans in Tibet, Beijing adamantly refused to recognize that there was any problem in Tibet. The only issue open for discussion, they said, was the Dalai Lama’s personal status and privileges. This despite His Holiness’ constant reminder that his own status or privilege is a non-issue as he needs “absolutely nothing” for himself and that he has in fact made an irrevocable decision to relinquish his traditional power and position under a new dispensation.

As the eighties wore on, hardliners in the Chinese power structure advocated retrograde policy in Tibet. With this came a new wave of repression, coupled by a demographic aggression of Tibet with thousands upon thousands of Chinese settlers.

Naturally, Tibetans in Tibet staged a series of independence demonstrations. Crushing the demonstrations with brutal force, Beijing used all occasions of “dialogue” with the exile leadership to blame His Holiness the Dalai Lama for fomenting instability in Tibet.

Then, in August 1993, China severed all formal contacts with the Tibetan leadership.

Nevertheless, His Holiness the Dalai Lama continued to reach out to the Chinese leaders through mutual friends. Appointing Lodi Gyari and Kalsang Gyaltsen as his envoys for achieving dialogue with China, he instructed them to make all efforts toward this end. In the event , the envoys managed to open an informal channel of communication through intermediaries.

Finally, formal contact was restored in September 2002 when China hosted a visit of a four-member delegation, consisting of the two envoys and their two aides.

Since then, there have been four more meetings: in 2003, 2004, 2005, and 2006.

Lodi Gyari, head of the Tibetan delegation, said the goals of his team were to: 1) Re-establish direct contact with the Chinese leadership and create a congenial atmosphere for regular face-to-meetings; 2) Explain His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s Middle Way Approach.

Gyari described the meetings with the Chinese as having taken place in an atmosphere of cordiality. The exchange of views, he said, was frank and spontaneous.

Returning from the fifth and latest round of discussions in February 2006, Gyari said that there is now “a better and deeper understanding of each other’s position” and recognition of the “fundamental differences” in the positions taken by the two sides.

But, “our Chinese counterparts made clear their interest in continuing the present process and their firm belief that the obstacles can be overcome through more discussions and engagements.”

Gyari did not specify what the differences were. As a matter of fact, none of his statements provided the specifics of the discussions. This, he later explained, was because China preferred to operate cautiously and free of scrutiny, particularly on sensitive issues like Tibet, and also because to “openly discuss the dialogue would adversely impact the process”.

Meanwhile, the Tibetan Government-in-Exile vowed to make every possible effort to help build trust with the Chinese leadership. Toward this end, Professor Samdhong Rinpoche, head of the exile government, made a number of public appeals to Tibetans and Tibet supporters to refrain from activities that would embarrass the Chinese leaders and hurt China’s national sensitivity.

In September 2005, when Hu Jintao was slated to visit Europe and America, he circulated a letter, appealing to Tibetans and Tibet supporters to desist from acts that would cause personal embarrassment to the Chinese leader and hurt China’s national sensitivity.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama supported Professor Rinpoche’s stand and urged Tibetans and international supporters to take note of Professor Rinpoche’s appeal.

Again, in April 2006, when Hu was scheduled to visit Canada and the US, Professor Rinpoche made a stronger appeal, this time asking Tibetans and supporters to refrain from protest demonstrations altogether.

Inexplicably, signals emerging from Beijing are becoming more belligerent. Vilification of His Holiness the Dalai Lama is reaching a fever pitch and the Tibetans in Tibet are being subjected to yet another round of repression.

In addition, the state-run website of the “China Tibet Information Center” published an article, condemning the Middle Way approach of the Dalai Lama as an attempt to “refute the current political system in Tibet”.

Widely advertised by Xinhua, the article thrashed His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s demand for what it called “one country, two systems” as unacceptable and counter to the Constitution and law of China. The Dalai Lama’s demand for “high-level autonomy or real autonomy with an elected Tibetan government in Lhasa” is not in keeping with his advocacy for Tibet to remain “within the framework of the Chinese Constitution”, the article said.

“China’s lack of trust in His Holiness the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan people is one of the most critical obstacles we currently face in our dialogue,” Gyari said.

Although, His Holiness has stated again and again that he is not seeking Tibet’s independence, China wants him to rewrite the history of Tibet and say that Tibet has always belonged to China. Since His Holiness cannot change the past history, he had said that he wanted to look to the future and reach a settlement that did not separate Tibet from China. But China is not convinced, it continues to suspect him of nursing a hidden agenda for Tibet’s independence.

This and other fundamental differences mean that coming to a negotiated settlement will not be easy, he said. However, having now “identified each other’s position and differences, it is our sincere hope that both the sides can start making serious efforts to find a common ground and build trust.

“In furtherance of this goal, His Holiness has made the offer to go personally to China on a pilgrimage. This has met with considerable opposition from Tibetans, both inside and outside Tibet, as well as from friends in the international community who are not convinced of China’s sincerity. But His Holiness is committed to doing everything he can to dispel the climate of mistrust that continues to exist.”

Gyari went on to say that His Holiness the Dalai Lama has a vision of the Tibetans being able to live in harmony within the People’s Republic of China.

“Today’s China was born out of an historical movement for people’s self-determination and the Constitution asserts that it is based on principles of equality. Let us build our relations on this equality and give the Tibetan people the dignity to freely and willingly be a part of this nation. We cannot re-write history, but together we can determine the future,” he said.