Tibetans in exile build new institutions as their spiritual leader leaves politics.

By AMY YEE

The Wall Street Journal (Opinion Asia)

June 10, 2011

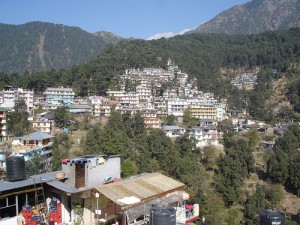

The Dalai Lama’s official role in the Tibetan exile administration has ended. The Central Tibetan Administration (CTA), based in Dharamsala in northern India, last week finalized changes to its charter that leaves the Tibetan spiritual leader without a formal position in the political affairs of Tibetan exiles, nearly 100,000 of whom live in India. It’s a terrifying prospect for the many Tibetans who rely on the Dalai Lama for political as well as spiritual guidance. But the move squarely challenges Tibetan exiles to strengthen a secular, democratic system first envisioned by the Dalai Lama decades ago.

Last week’s amendments to the charter were put forward by the Dalai Lama himself, who since 2001 has talked of his semi-retirement from political responsibilities. This left many Tibetans—leaders and ordinary exiles alike—anxious and disheartened about the future. The exile administration’s cabinet issued a last-ditch appeal on May 24 to the Dalai Lama to remain ceremonial head of the government. The Dalai Lama flatly rejected the offer. A few days later, the new charter was ratified.

Of course, the Dalai Lama won’t retire from being a spiritual leader and the 14th reincarnation of the Buddha of compassion. He will still provide advice and encouragement and work toward “a satisfactory solution to the question of Tibet.” The CTA’s charter still defines him as “the most revered leader who has inherent responsibility to speak for Tibet and Tibetan people.” The Dalai Lama will still meet with world leaders to speak on behalf of the Tibetan people. His breakneck travel schedule of Buddhist teachings, appearances and meetings around the world will remain packed.

But the changes in the charter are real. The Dalai Lama now has no legal or constitutional responsibilities or obligations. He cannot dismiss the exile administration’s parliament or sign new bills into law. A regency council that, if he passed away, would have been in charge until a 15th reincarnation was named, was annulled.

Instead, responsibility will fall to the exile administration headed by an elected prime minister. In this sense, Lobsang Sangay, the 43-year-old scholar who won elections for the post this spring, will have more responsibility than any other exile-administration prime minister when he is sworn in this August.

The Dalai Lama’s “remarkable decision,” as he called it, is the latest step in an effort to devolve power and establish a democratic government in exile. Mr. Sangay knows much about the decades-long process; he wrote his doctoral dissertation at Harvard Law School on the subject.

In 1960, only a year after being exiled to India, the Dalai Lama suggested an elected parliament, which bewildered Tibetans. “Why do we need that? We have you,” many wondered, according to Mr. Sangay.

A 1961 document that was the basis of a draft constitution outlined the possibility for the Dalai Lama to be impeached. The suggestion shocked Tibetans, but the Dalai Lama insisted the clause remain in the 1963 constitution. The next radical suggestion came later that decade when the Dalai Lama pushed for more representation by women in the exile administration. More steps followed, including the formation of ministries, a judiciary and elections for prime minister of the CTA in 2001.

Critics say the exile administration is fragmented, bureaucratic and prone to infighting (not unlike most governments). The administration itself has long admitted that it is not a full-fledged government; in another notable change in the charter, that is now official. It now defines itself as an “administration,” not an exile government. That has always been the official name in English, but now the wording has changed in Tibetan to something closer to “administration” as well.

Ostensibly, this creates less cause for conflict between India and neighboring China, where relations are already tense. However, some Tibetan activists are dismayed by this change, which they see as disempowering the exile administration and the Tibetan movement in general. In a defiant move, Tibetan Youth Congress, the largest pro-Tibet NGO, earlier this week vowed to retain the government-in-exile name.

To add further concerns of rendering the Tibetan movement toothless, a Chinese official in May said China would refuse to negotiate with Mr. Sangay, instead only speaking to the Dalai Lama’s envoys.

Mr. Sangay says it is the outcome of negotiations that matters, not the process. Let China continue talks with the Dalai Lama’s envoys, he says. Yet he underscores his commitment to dialogue with Chinese people. During his years at Harvard Mr. Sangay organized conferences attended by Tibetans and Chinese scholars, including members of Communist Party think tanks, to foster dialogue between the two sides.

Still, the Chinese are not exactly reciprocating. Zhu Weiqun, a senior Chinese official last month called Mr. Sangay and the exile administration “a separatist political clique that betrays the motherland.” Mr. Sangay’s response? “The allegations are part of their script,” he replies. “I believe in a nonviolent, peaceful way to solve the issue. We’ve always extended our hand. We are still willing.”

Challenging as the road ahead may be for the exile administration, at the very least Mr. Sangay’s story might serve as an example of merit and democratic values. Unlike the current prime minister, a highly respected reincarnation of a high monk, Mr. Sangay hails from a modest background and worked his way up against the odds. He grew up in a refugee settlement in the northeast Indian city of Darjeeling and went to a Tibetan refugee school. His parents eked out a living on one acre of land. To pay his school fees they sold one of their three cows. Mr. Sangay, who speaks Tibetan, English and Hindi, went on to study law at Delhi University and won a Fulbright grant to Harvard Law School.

Talks with China remain at an impasse, and news of repression continues to seep out of Tibet. The future is uncertain, but Tibetans in exile must step up to the challenge of running and supporting their new administration without the Dalai Lama. After all, it is the only choice he has left them.

—Ms. Yee is a journalist based in New Delhi.