dalailama.com

October 9, 2013

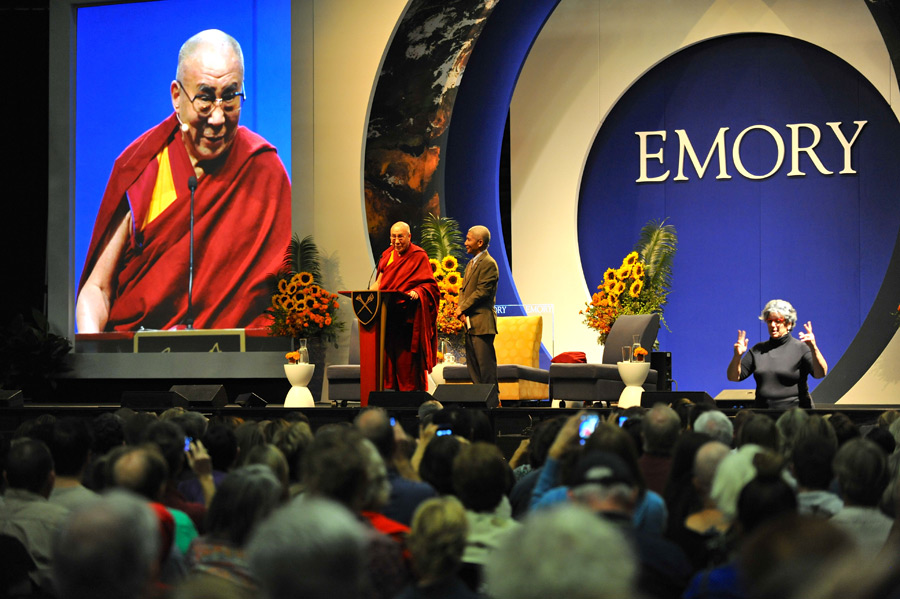

Atlanta, Georgia, USA, 8 October 2013 – Amidst the flashing blue and red lights of the secure motorcade, the roar of motorcycle outriders and the clatter of a helicopter overhead, His Holiness the Dalai Lama drove from his hotel in Atlanta out to the Gwinnet Arena, venue of the day’s programs. He was met at the door by Emory University President James Wagner and greeted by the audience in the 10,000 seat arena with warm and friendly applause.

In his introduction, President Wagner mentioned that Emory University was founded by Methodists and has long been motivated to prepare citizens for life not only to do well, but also to do good. Paul Wolpe, the moderator, followed him saying that a university concerns itself with knowledge, but there is also a need for wisdom, deep understanding and insight. Therefore, he said, it was a rare privilege to be in the presence of someone who possesses wisdom, as he invited His Holiness to speak.

His Holiness had hardly begun when he saw his friend Richard Moore arriving and left the stage to greet him.

“His example is really something,” he said, “as a 10 year old boy in Northern Ireland he lost his sight when struck by a rubber bullet, but was forgiving about it, showed no anger. I talk about compassion, ‘blah, blah, blah’, but he puts it into effect. He’s my hero.”

Coming back to the topic of secular ethics, His Holiness said we have to look at humanity and human history to see why they are necessary. Pointing out that people like him over 50 years old belong to the twentieth century, a time past, but those who are 15, 20 or even 30 years old belong to the twenty-first century and have the future before them. He asked for a show of hands to see how many of the younger generation were there.

“Historians say 200 million people died violently during the twentieth century, despite many wonderful developments, it was a period of bloodshed and violence. I believe that if we think of others as our human brothers and sisters there will be no room to cheat, deceive and fight them. We need to change our way of solving problems and conflicts; instead of force we need to rely on dialogue. We need to think less of ‘them’ and ‘us’ and take others into account. There will always be sources of conflict between us, but when they arise we need to talk them through not fight about them.”

He said we need to make this new century a century of compassion. He distinguished two kinds of compassion: an instinctive response that derives from biological factors rooted in the affection we receive as infants from our mothers and a more extensive, inclusive compassion supported by reason.

“Nowadays we are so interdependent that the destruction of our neighbours means our own destruction too. This is why we have to think of building a more compassionate society and we need to do it less on the basis of faith than on reasoning. If we apply common sense we can see that among our neighbours families who love and trust each other greet others in a friendly way. On the other hand, even when a family is materially better off, if they lack warm feelings for each other, if they are jealous and mistrustful, moved by suspicion, they’re not very happy.”

He went on to cite scientific findings that suggest that suspicion, anger and fear have the effect of eating away at our immune system. To ensure our physical health we need peace of mind. Therefore, just as we need to observe physical hygiene to stay well, we need to develop emotional hygiene too.

“Society will not be changed by UN intervention or by rulings from Capitol Hill. Society is made up of individuals, so change must start with individuals. Change will come not from giving or spending money, but from changing our minds. We can overcome our problems by applying secular ethics based on common sense, common experience and scientific findings. Thank you – now questions.”

To a question about challenges in the twenty-first century His Holiness replied that education is a key factor in the creation of a happier more peaceful world. He said we need to design education that provides for both knowledge and a healthy mind. In addition, we have to ask if the present American lifestyle is ultimately sustainable. And we have to create a sense of compassion that responds to all humanity.

“We need to think of humanity as one big family; if they are happy, I’ll be happy. Too much competitiveness leads to jealousy and suspicion of your neighbours, which in turn leads to further mistrust. How can we be happy then? This is common sense.

“Education about secular ethics is not only about compassion, but also about understanding the mind. We need a map of the mind to understand how the mind works; and we can train the mind through mindfulness.”

Asked whether it seems that discernment was better developed in the West and compassion better developed in the East, His Holiness denied such divisions saying that human beings in both part of the world are the same, have the same emotions and so on. To a question about compassion on a global or political level, he cited the example of the European Union which came together motivated by a sense of the greater importance of its members’ common interests rather than their individual concerns.

His Holiness was asked if acts of compassion make you feel good, are they really altruistic? He answered that helping others does bring us benefit. We do have self interest, we are selfish, but we need to be wisely selfish not foolishly selfish. He mentioned as examples that while taking drugs is foolishly selfish, taking exercise is wisely selfish. As social animals we need to cooperate, which means we need trust, and that is based on our having concern for others’ well-being.

A mother of two young boys wanted to know how compassion could help them. His Holiness replied:

“I have a certain amount of compassion and it began with my mother, an illiterate, uneducated village woman, who was essentially warm-hearted. Today, when there is a greater need for warm-heartedness, which women have a special capacity for, as scientific findings have confirmed, we need more female leadership.”

At the end of the morning session, His Holiness requested those listeners who found what he had said interesting to think more about it, to discuss it with friends and if it seemed meaningful to put it into effect. He told those who didn’t find it interesting not to worry, but to forget it when they left the hall.

After lunch, he met key members of the Emory-Tibet Medical Science Initiative and Tibetan Medicinal Research who explained some of the scientific research they are conducting on Tibetan medicine.

Back in the Arena for a panel discussion on ‘Secular Ethics and Education’ His Holiness remarked that while modern science has tended to focus on material, measurable things, mind is also part of reality, so science should include mind and the emotions in its field of study. He noted that many of the problems we face are our own creation and their source is not something physical; the trouble maker is within us. He mentioned the issue of gun control, saying that it is less the gun that causes trouble than the human being wielding it. What is essential is mental control. A weapon can have a protective function; the real source of trouble is our destructive emotions.

“Destructive emotions like anger and fear destroy our peace of mind and when our peace of mind is gone, our physical well-being is gone too. Through education and awareness we can learn to reduce our negative emotions. I have been working with scientists, like Richie Davidson here, who has been studying this for 20-30 years, not for wealth or fame, but to make the world a better place. And I’d like to thank them very much and ask them to keep it up.”

Richie Davidson wanted to share three important points that show that even young infants prior to education respond positively to generosity, to scenes where help rather than hindrance is given to someone else. He said that just as we all have a capacity for language, but have to exercise it to bring it to fruit, we also have a capacity for compassion, but similarly have to develop it. Frans de Waal added that while it is true that competitiveness and aggression are present in nature, if you live in groups, you have to compromise and care for others.

His Holiness responded that here was evidence of the importance of education. First we need awareness and then conviction and on that basis our behaviour will be more open, truthful and transparent.

Geshe Lobsang Tenzin Negi talked about compassion as the foundation for secular ethics and described scientific findings that support this. They reveal evidence that compassion can be taught, and we can train to regulate our emotions. Brooke Dodson-Lavelle spoke of the importance of recognizing that children worry about being excluded, they need to feel loved to be able to extend compassion to others. This is why it is true to say that it takes a full community to bring up a child.

His Holiness responded to a question about the role of religion by explaining that the major religions have had and will continue to have a role in fostering qualities like love and compassion. However, each religion has limits or boundaries and what we need today is a sense of ethics that goes beyond such boundaries. Hence the need for secular ethics.

Before the day’s discussions came to an end, President Wagner presented certificates of appreciation to Geshe Lobsang Tenzin Negi and his mentor Dr Robert Paul for their work in co-ordinating the Emory-Tibet Partnership, which has given rise to the Robert A Paul Emory-Tibet Science Initiative. His Holiness added his own appreciation that like himself Geshe la came from a remote village, and has proved to be very useful.

Arthur Zajonc, President of Mind & Life Institute brought the session to a conclusion, acknowledging the inspiration he and his colleagues found in His Holiness’s sense of precision in thought and observation. He remarked that they continue to work to bring together the reality within us with the reality around us. An example is the project to introduce science into Tibetan monasteries. He ended by quoting the French philosopher Simone Weil: