July 14th, 2014 Posted in Tibet in Exile

By Gavin Kilty*

Having never been to Tibet before, I had built up a multitude of impressions of what it would be like. Some of those impressions were reinforced during my visit this summer while others were challenged by the actual experience of being there.

One Chinese professor from Shanghai recently said, “The Communist Party is like God. It is everywhere. You just can’t see it.” This was my overall impression of Chinese rule in Tibet. It is the rule of the iron fist, yet you never see who the fist belongs to. During our visit, we confronted many examples of this tight control.

No foreigner can travel in Tibet without a guide. This guide must be organized before entering the country. Whether traveling alone or in a group, a guide is mandatory. It does not mean that the guide has to follow the tourists as they wander through the streets of towns, but he must organize and report the itinerary to the authorities regularly at check points positioned along the main highways.

As well as a guide and a Chinese visa, additional permits must be obtained for Tibet in general and for many of the areas to be visited. The entire trip itinerary together with names and passport numbers must be submitted to the authorities and on no account can it be changed. For example, one person in our group fell sick and considered flying back to Kathmandu from Lhasa. This would have meant reapplying for an adjustment to the entire group itinerary, requesting that one name be removed from the list, and applying for a permit for that person to leave the country early. One cannot simply book a flight, take a taxi to the airport, and leave.

For Tibetans the daily life situation is worse. In the so-called Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), Tibetans cannot move or travel from one town or region to another without permission. A Tibetan from Shigatsé wanting to visit relatives in Lhasa must apply to authorities for permission to do so – and this in their own country! Moreover, if a Tibetan has a relative staying in his or her house, Chinese officials must be notified of that visit. Freedom of movement is a fundamental human right, and it is just one of the freedoms curtailed in the TAR.

Since 2008 it has become very difficult for Tibetans to obtain a visa for India. One woman whose uncle lives in Dharamsala, told me she can no longer visit him there because of her past trips abroad. She even suggested that her son, who had done excellently at school, was being denied the opportunities to pursue his chosen career because of his mother’s connections with people living outside of Tibet.

Everywhere we travelled during our tour, there were permits to check, passports to show, and places that were off-limits for no apparent reason. The beautiful Lama Latsho Lake with its prognostic abilities was suddenly out of bounds for tourists over the month of Saga Dawa. Why? What possible threat to national security could a lake pose?

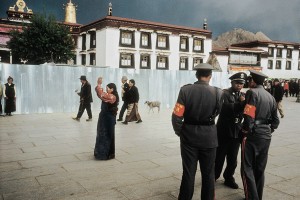

Control was everything. People watched us closely as we made our way through the Potala alongside throngs of Chinese tourists/pilgrims. Once, in a street in Lhasa, a Tibetan shopper was arguing with a Chinese stallholder over the price of an item. Within minutes a plain-clothes security official arrived from nowhere to sort it out.

Even at Everest base camp, a haven of peace and tranquility miles from any political centre, checkpoints were in evidence. We couldn’t do this and we couldn’t do that. We could not even walk alone from the guest house to the base camp tents.

Young military officers are everywhere. Some are pleasant, others officious. Most carry guns. Most look about seventeen years old. In Lhasa there is a police check post every hundred metres or so.

As we approached the full moon of Saga Dawa, lines of army trucks appeared on the streets, each filled with baby-faced soldiers facing to the outside of the truck, machine gun in hand, just waiting for trouble to begin.

The Chinese system functions by way of a tight control over its citizens. Although outwardly it has the appearance of a rampant capitalistic country, its system of social control comes straight out of the old Soviet model handbook. This is explained in the excellent book, The Party: The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers, by Richard McGregor. Centralization and control of all aspects of life is the driving force behind China’s presence in Tibet. It does not matter if individuals (the relatives of the Tibetan self-immolators, for example) are harmed in the process. The system comes first. What does it matter if a few ants die as long as the ant colony is preserved? Public opinion is to be controlled and even repressed if necessary, all to ensure the well-being and survival of the Communist Party. Survival is at the very heart of the Communist Party’s thinking. Devoid of any mandate from the people, it must exercise an iron will at any cost.

The Tibetan people are victims of this repressive system. They are not regarded as a distinct people with sensitivities and needs, but as beneficiaries of the Motherland who must comply with the will of the Party. Anything other than that is unpatriotic at the least and treachery at the worst.

Take the issue of the Dalai Lama. No photo of him is allowed anywhere in Tibet. No book, no video, nothing that carries his name is allowed. This is a deliberate attempt to wipe his existence from the consciousness of the Tibetan people. China’s leaders know full well that the Tibetan people love and adore the Dalai Lama. They know, or at least they should know, that he is not a “terrorist” or a “wolf in sheep’s clothing.” And yet they pursue their cruel policy. Why? The answer is control. By separating the Tibetan people from a leader of their own, China’s leaders hope to extinguish any sparks of rebellion or protest. There is no empathy for the Tibetan people. The self-immolators and their families deserve no pity and no understanding, because their actions threaten the unity of the Motherland. Therefore, they are treated with harshness instead of understanding.

When the current Chinese president, Xi Jinping, was visiting Europe recently he said, in response to a question about the Chinese government’s lack of care for the Tibetan people, “The Chinese government cares more for the Tibetan people than the international community does.” From one point of view he was correct. The government has poured billions of yuan into Tibet to bolster its economy, improve infrastructure, and provide services. There are even stories of the government building homes for Tibetans who return from exile, and of providing them with jobs and money. Monasteries have been rebuilt; hospitals and schools are constructed where there were none before. These improvements in Tibet are undeniable. The country resembles a large construction site. This is what the president meant when he said the government cares for Tibetans.

What the questioner meant however, and what the international community refers to when it raises issues around “caring for Tibetans”, is something different. They seek the restoration of basic human rights, a return of political power, and the enjoyment of basic freedoms that have been denied.

I do not know how most Tibetans would react if given a choice between economic empowerment, jobs, and housing on one hand, and the restoration of political freedoms and human rights they once enjoyed on the other. Perhaps many would pragmatically opt for the former over the latter. Regardless of personal preference, the right to be able to move as you please, worship as you please, speak as freely as you please, to have the autonomy that all people deserve, to be able to stand up against injustice, oppression and occupation are the fundamental rights of every being on the planet.

The Tibetan people deserve no less. They are denied it. This is their struggle. It is not built on hate, ideology, nationalism, religious bigotry, or even nostalgia for the past. It stems from the pursuit of justice and fairness, and for everything that is decent in this world.

Long may the Tibetan people survive. Long may they stand firm against the tyranny cast over them, and may truth, justice and liberty prevail. Bö gyal lo! Bö gyal lo! Bö gyal lö!

*Gavin Kilty lived in Dharamsala, India, for fourteen years. He spent eight years training in the traditional Geluk monastic curriculum at the Institute of Buddhist Dialectics. Currently Gavin is a translator for the Institute of Tibetan Classics and also teaches Tibetan language courses in India, Nepal, and elsewhere.