A Historical Overview of Tibet by Michael Van Walt Praag

The Tibetan Government-in-Exile, headed by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Tibet’s exiled head of state and spiritual leader, has consistently held that Tibet has been under illegal Chinese occupation since China invaded the independent state in 1949/50. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) insists that its relation with Tibet is purely an internal affair, because Tibet is and has been for centuries an integral part of China. The question of Tibet’s status is essentially a legal question, albeit one of immediate political relevance.

The PRC makes no claim to sovereign rights over Tibet as a result of its military subjugation and occupation of Tibet following its armed invasion in 1949/50. Indeed, the PRC could hardly make that claim, since it categorically rejects as illegal claims to sovereignty put forward by other states based on conquest, occupation, or the imposition of unequal treaties. Instead, the PRC bases its claim to Tibet solely on the theory that Tibet became an integral part of China 700 years ago.

Early History

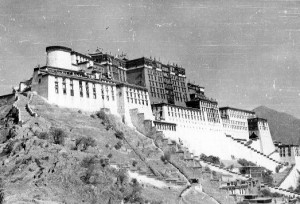

Although the history of the Tibetan state started in 127 B.C., with the establishment of the Yarlung Dynasty, the country as we know it was first unified in the 7th Century A.D., under King Songtsen Gampo and his successors. Tibet was one of the mightiest powers of Asia for the three centuries that followed, as a pillar inscription at the foot of the Potala Palace in Lhasa and Chinese Tang histories of the period confirm.

A formal peace treaty concluded between China and Tibet in 821/823 demarcated the borders between the two countries and ensured that, “Tibetans shall be happy in Tibet and Chinese shall be happy in China.”

Mongol Influence

As Genghis Khan’s Mongol Empire expanded towards Europe in the West and China in the East in the 13th Century, Tibetan leaders of the powerful Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism concluded an agreement with the Mongol rulers in order to avoid the conquest of Tibet. The Tibetan Lamas promised political loyalty and religious blessings and teachings in exchange for patronage and protection. The religious relationship became so important that when, decades later, Kublai Khan conquered China and established the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368), he invited the Sakya Lama to become the Imperial Perceptor (sic) and supreme pontiff of his empire.

The relationship that developed and continues to exist into the 20th Century between the Mongols and Tibetans was a reflection of the close racial, cultural, and especially religious affinity between the two Central Asian peoples. The Mongol Empire was a world empire and, whatever the relationship between its rulers and the Tibetans, the Mongols never integrated the administration of Tibet and China or appended Tibet to China in any manner. Tibet broke political ties with the Yuan emperor in 1350, before China regained its independence from the Mongols. Not until the 18th Century did Tibet again come under a degree of foreign influence.

Relations with Manchu, Gorkha and British Neighbors

Tibet developed no ties with the Chinese Ming Dynasty (1386-1644). On the other hand, the Dalai Lama, who established his sovereign rule over Tibet with the help of a Mongol patron in 1642, did develop close religious ties with the Manchu emperors, who conquered China and established the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). The Dalai Lama agreed to become the spiritual guide of the Manchu emperor, and accepted patronage and protection in exchange. This “priest-patron” relationship (known in Tibetan as Choe-Yoen), which the Dalai Lama also maintained with some Mongol princes and Tibetan nobles, was the only formal tie that existed between the Tibetans and Manchus during the Qing Dynasty. It did not, in itself, affect Tibet’s independence.

On the political level, some powerful Manchu emperors succeded in exerting a degree of influence over Tibet. Thus, between 1720 and 1792, Emperors Kangxi, Yong Zhen, and Qianlong sent imperial troops to Tibet four times to protect the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan people from foreign invasions by Mongols and Gorkhas or from internal unrest. These expeditions provided the Emperor with the means for establishing influence in Tibet. He sent representatives to the Tibetan capital, Lhasa, some of whom successfully exercised their influence, in his name, over the Tibetan Government, particularly with respect to the conduct of foreign relations. At the height of Manchu power, which lasted a few decades, the situation was not unlike that which can exist between a superpower and a satellite or protectorate, and therefore one which, though politically significant, does not extinguish the independent existence of the weaker state. Tibet was never incorporated into the Manchu Empire, much less China, and it continued to conduct its relations with neighboring states largely on its own.ective by the time the British briefly invaded Lhasa and concluded a bilateral treaty with Tibet, the Lhasa Convention, in 1904. Despite this loss of influence, the imperial government in Peking continued to claim some authority over Tibet, particularly with respect to its international relations, an authority which the British imperial government termed “suzerianity” in its dealings with Peking and St. Petersburg, Russia. Chinese imperial armies tried to reassert actual influence in 1910 by invading the country and occupying Lhasa. Following the 1911 revolution in China and the overthrow of the Manchu Empire, the troops surrendered to the Tibetan army and were repatriated under a Sino-Tibetan peace accord. The Dalai Lama reasserted Tibet’s full independence internally, by issuing a proclamation, and externally in communications to foreign rulers and in a treaty with Mongolia.

Tibet in the 20th Century

Tibet’s status following the expulsion of Manchu troops is not subject to serious dispute. Whatever ties existed between the Dalai Lamas and the Manchu emperors of the Qing Dynasty were extinguished with the fall of that empire and dynasty. From 1911 to 1950, Tibet successfully avoided undue foreign influence and behaved in every respect as a fully independent state.

Tibet maintained diplomatic relations with Nepal, Bhutan, Britain, and later with independent India. Relations with China remained strained.

The Chinese waged a border war with Tibet while formally urging Tibet to “join” the Chinese Republic, claiming all along to the world that Tibet was one of China’s five races. In an effort to reduce Sino-Tibetan tensions, the British convened a tripartite conference in Simla in 1913 where the representatives of the three states met on equal terms. As the British delegate reminded his Chinese counterpart, Tibet entered into the conference as an “independent nation recognizing no allegiance to China.” The conference was unsuccessful in that it did not resolve the differences between Tibet and China. It was, nevertheless, significant in that Anglo-Tibetan friendship was reaffirmed with the conclusion of bilateral trade and border agreements. In a Joint Declaration, Great Britain and Tibet bound themselves not to recognize Chinese suzerainty or other special rights in Tibet unless China signed the draft Simla Convention which would have guaranteed Tibet’s greater borders, its territorial integrity and full autonomy. China never signed the Convention, however, leaving the terms of the Joint Declaration in full force.

Tibet conducted its international relations primarily by dealing with the British, Chinese, Nepalese, and Bhutanese diplomatic missions in Lhasa, but also through government delegations traveling abroad. When India became independent, the British mission in Lhasa was replaced by an Indian one. During World War II Tibet remained neutral, despite combined pressure from the United States, Great Britain, and China to allow passage of raw materials through Tibet.

Tibet never maintained extensive international relations, but those countries with whom it did maintain relations treated Tibet as they would any sovereign state. Its international status was no different from, say, that of Nepal. Thus, when Nepal applied for membership in the United Nations in 1949, it cited its treaty and diplomatic relations with Tibet to demonstrate its full international personality.

The Invasion of Tibet

The turning point in Tibet’s history came in 1949, when the People’s Liberation Army of the PRC first crossed into Tibet. After defeating the small Tibetan army and occupying half the country, the Chinese government imposed the so-called “17-Point Agreement for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet” on the Tibetan government in 1951. Because it was signed under duress, the agreement lacked validity under international law. The presence of 40,000 troops in Tibet, the threat of an immediate occupation of Lhasa, and the prospect of the total obliteration of the Tibetan state left Tibetans little choice.

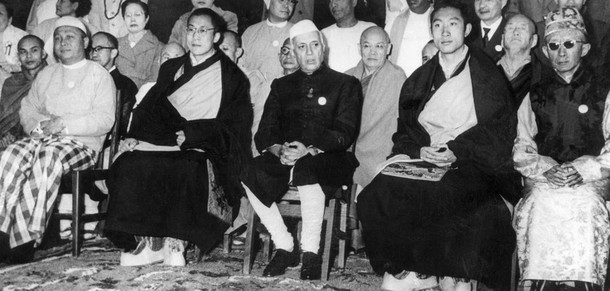

As open resistance to the Chinese occupation escalated, particularly in Eastern Tibet, the Chinese repression, which included the destruction of religious buildings and the imprisonment of monks and other community leaders increased dramatically. By 1959, popular uprisings culminated in massive demonstrations in Lhasa. By the time China crushed the uprising, 87,000 Tibetans were dead in the Lhasa region alone, and the Dalai Lama had fled to India.

In 1963 the Dalai Lama promulgated a constitution for a democratic Tibet. It has been successfully implemented, to the extent possible, by the Government-in-exile.

See also: Invasion & After

Conclusion

In the course of Tibet’s 2,000-year history, the country came under a degree of foreign influence only for short periods of time in the 13th and the 18th centuries. Few independent countries today can claim as impressive a record. As the ambassador of Ireland at the UN remarked during the General Assembly debates on the question of Tibet, “[for thousands of years, or for a couple of thousands of years at any rate, [Tibet) was as free and fully in control of its own affairs as any nation in this Assembly, and a thousand times more free to look after its own affairs than many of the nations here.”

Numerous other countries made statements in the course of the UN debates that reflected similar recognition of Tibet’s independent status. Thus, for example, the delegate from the Philippines declared, “It is clear that on the eve of the invasion in 1950, Tibet was not under the rule of any foreign country.” The delegate from Thailand reminded the assembly that the majority of states “refute the contention that Tibet is part of China.” The United States joined most other UN members in condemning Chinese aggression and invasion of Tibet. In 1959, 1960, and 1961, the UN General Assembly passed resolutions (1353 (XIV), 1723 (xvi), and 2079 (XX)) condemning Chinese human rights abuses in Tibet and calling on that country to respect the fundamental freedoms of the Tibetan people, including their right to self-determination.

From a legal stand point, Tibet has to this day not lost its statehood. It is an independent state under illegal occupation. Neither China’s military invasion nor the continuing occupation by the PLA has transferred the sovereignty of Tibet to China. As pointed out earlier, the Chinese government has never claimed to have acquired sovereignty over Tibet by conquest. Indeed, China recognizes that the use or threat of force (outside the exceptional circumstances provided for in the UN Charte), the imposition of an unequal treaty or the continued illegal occupation of a country can never grant an invader legal title to territory. Its claims are based solely on the alleged subjection of Tibet to a few of China’s strongest foreign rulers in the thirteenth and eighteenth centuries.

How can China – one of most ardent opponents of imperialism and colonialism – defend its continued presence in Tibet against the wishes of the Tibetan people by citing Mongol and Manchu imperialism and its own colonial policies as justification?